Biodiversity in California

California is home to more than 5000 species of native plants. If one recognizes all of the different subspecies that exist in California, the native flora includes approximately 6500 minimum-rank taxa (species, subspecies, and varieties; Jepson eFlora, 2015). To put this in perspective, this is more than exist in any other state in the nation, and more than exist in all of Canada (Kartesz, 2015; USDA PLANTS database, 2015).

|

The term "native" |

|

Although species have always migrated around the world, the rate of movement (and subsequent impacts on species already in an area) increased dramatically when Europeans began colonizing distant parts of the world. For plants, we use the same rule-of-thumb that we use for humans: a "native" group is a group that existed in a place before this rapid movement began. |

Although most of the plant species and subspecies in California are native (having existed in California before the arrival of Europeans), a number of introduced or alien plant species have become naturalized and firmly established in the wild. Those that become invasive often pose threats to native species, outcompeting them for resources or changing the environment in other ways that harm them.

More than a quarter of the native plant species in California are endemic to California, existing nowhere else on Earth (Harrison 2013). Species that are endemic to a relatively small area are generally of greater conservation concern than other species: if they are extirpated (eliminated from that local area), the species is extinct. In contrast, if a widespread species is extirpated from the same small area, it still exists somewhere else on Earth. Of all the plant taxa that are native to the United States, Canada, and Greenland combined, over 5% are endemic (restricted) to Hawai'i and over 9% are endemic to California (Imada, 2012; Jepson eFlora, 2015; Kartesz, 2015; USDA PLANTS database, 2015). The California Native Plant Society maintains inventories of rare plants in California: there are currently 22 that are considered extinct or that have not been seen in the wild in at least 20 years (CNPS Rare Plant Program, 2014).

Why are there so many plant species in California? -- California spans a large range of latitudes, from the Mexican border to Oregon, and a large range of elevations, from Death Valley (the lowest point in the United States,) to Mount Whitney (the highest point outside of Alaska). There is wide variation in rainfall across the state, from an annual average of less than 3 inches per year in Death Valley to an annual average of approximately 100 inches per year in some spots along the northwest coast of California. In addition, a wide range of soil types exists in the state. The resulting environmental variation helps explain why California supports so many different types of species.

Why are so many plant species endemic to California? – Part of the reason is that much of California has a climate that is found only in a few places on Earth: a mediterranean climate.

Most of California (but not all) has a mediterranean climate, with hot, dry summers and cool, wet winters. Annual rainfall is usually between 14 and 35 inches per year. High-elevation mountain areas may regularly receive snow during the winter, but still experience dry summers. To the east of California's major mountain chains, there are deserts. Deserts have lower rainfall (usually less than 10 inches per year), lacking the heavy winter rains that typically occur in a mediterranean climate. Potential evaporation in deserts (the amount of water that would evaporate if it were available) is higher than the rainfall received.

Only five regions on Earth have a mediterranean climate. These five regions are on different continents (on the west coasts of continents between 30 and 40 degrees north and south), and each has a unique set of species.

The California Floristic Province , which includes the non-desert regions of California plus bits of adjacent land in Oregon and northern Baja California, is considered a biodiversity hotspot. A "biodiversity hotspot" is defined as an area with high levels of endemism and a high threat of extinction. To be recognized as a biodiversity hotspot, a region must meet two criteria:

The California Floristic Province , which includes the non-desert regions of California plus bits of adjacent land in Oregon and northern Baja California, is considered a biodiversity hotspot. A "biodiversity hotspot" is defined as an area with high levels of endemism and a high threat of extinction. To be recognized as a biodiversity hotspot, a region must meet two criteria:

The 36 currently recognized biodiversity hotspots cover only about 2.4% of the Earth's land surface, but contain over half the plant species on Earth. The California Floristic Province is one of these hotspots.

California's deserts also contain rare plant and animal species, some of which have very narrow ranges. These deserts, however, are not currently part of a biodiversity hotspot, as defined above.

Among the threats to biodiversity in California are habitat loss (caused by numerous factors), water consumption, and impacts of introduced, non-native species.

Part of the reason for the diversity of plant species in California is the wide diversity of climates and soil types that exist in California. This creates different environments that support different species.

Climate varies with latitude, altitude, proximity to the ocean, and placement of mountains with respect to prevailing winds.

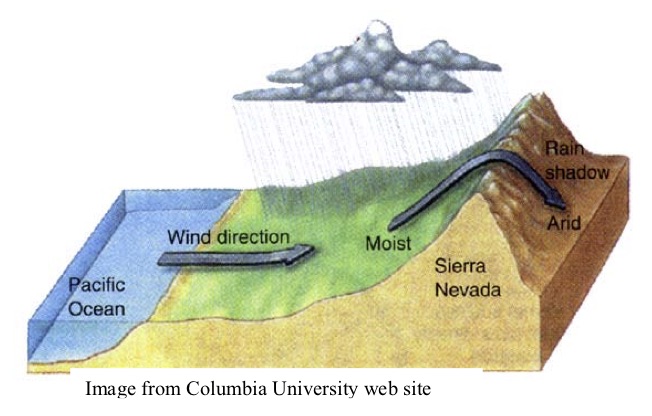

The mountains also cast rain shadows, creating a relatively wet area on the windward side of the mountain and a dry area (the rainshadow) on the leeward side of the mountain:

Rainshadows are caused when air is forced over mountains. As air travels up the windward side, it cools. As it cools, water condenses out of it, and it tends to rain on the windward side. The air descending the leeward side is relatively dry (having dropped its moisture already on the windward side). This causes the area on the leeward side of the mountain to be relatively dry. The Great Basin is a huge rainshadow between the Sierras and the Rocky Mountains.

The ocean along the coast of California moderates temperature swings. The cold current coming from the north along the coast also produces fogs. These fogs are observed in the summer in southern California and are very pronounced along the northern coast where you find redwood forests.

The line of mountains formed by the Cascades, the Sierra Nevada, and the transverse ranges, separates "cismontane" California from "transmontane" California. The cismontane region is on the west side of this dividing line, toward the ocean. Most of this region has a Mediterranean climate (described below). The transmontane region, in a rainshadow, is drier and is desert (cold desert or hot desert, depending on latitude). The highest elevations in California, with coldest temperatures, may be classified as having a type of highland climate.

The line of mountains formed by the Cascades, the Sierra Nevada, and the transverse ranges, separates "cismontane" California from "transmontane" California. The cismontane region is on the west side of this dividing line, toward the ocean. Most of this region has a Mediterranean climate (described below). The transmontane region, in a rainshadow, is drier and is desert (cold desert or hot desert, depending on latitude). The highest elevations in California, with coldest temperatures, may be classified as having a type of highland climate.

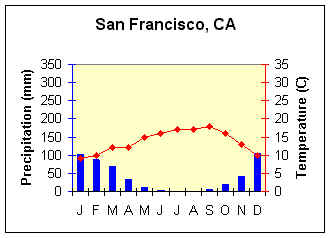

Mediterranean climates are sometimes described as having mild, moist winters and sometimes described as having cool, moist winters. They are always described as having a summer drought.

In the grand scheme of things, winter temperatures are mild; snow is rare. However, from the plant's perspective, a Mediterranean climate presents a challenge because, when temperatures are warm enough for rapid growth, water is rarely available, and when water is available for growth, temperatures are too low for rapid growth. Typically, a lot of the growth in this climate takes place in the spring, as temperatures begin to warm up, but before the soil water has disappeared. Germination of annuals may occur with the first rains of fall, but plants generally remain small and don't grow rapidly until temperatures warm up in the spring.

Soils vary in fertility, in the amount of water they can hold, and in the potentially stressful elements they contain (e.g., salts and heavy metals). California contains a wide variety of soil types, from thin rocky soils on steep mountain sides, to deep alluvial soils that have accumulated in valleys (and support some of the most productive agriculture on Earth), to salt flats in the desert, and serpentine soils near faults (which have high levels of heavy metals and low nutrients). Since different plant species have different abilities to cope with different conditions and stressors, this soil variation contributes to the fact that California contains many plant species.

Although climate and soil variation can help explain why there are so many plant species in California, it does not completely explain why so many are endemic or restricted to California. Endemic species can be classified as paleoendemics (species that were once widespread, but are now restricted to California) or neoendemics (species that originated or evolved here).

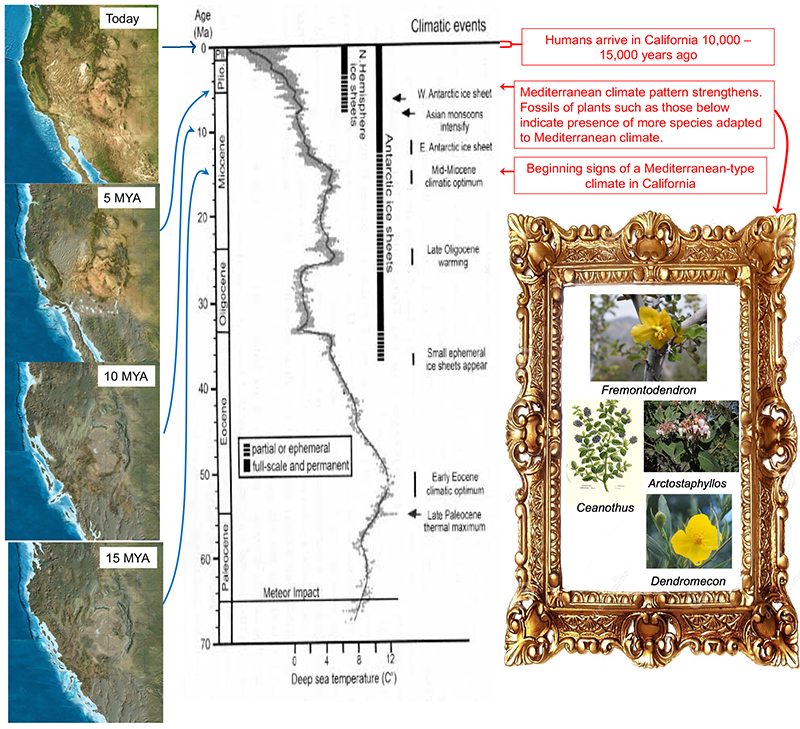

California has not always had the topography and climates it has today. Global climate has changed, mountains have risen, plateaus have collapsed, and the oceans have fallen and risen.

The graph in the image below shows global temperature change from long ago (at the bottom) to today (at the top). The left panels show geologic changes over time (maps from cpgeosystems.com). These show most of cismontane California emerging from under the ocean. They also show the collapse of the Great Basin (now desert areas between Sierras and the Rocky Mountains). That area was once a higher plateau that was cooler and more mesic (moist) than it is today. With its collapse and the rise of the Sierra Nevada, the Great Basin dried and species that once flourished there could no longer survive.

Paleoendemics are species that were once more widespread, but are now confined to California.

Some species lost much of their habitat as climate changed. However, due to California's large variation in climate, topography, etc., it contains small regions where some of these species can still survive. Two famous examples of paleoendemics are the coast redwood (Sequoia semperviron) and the giant sequoia (Sequoiadendron giganteum).

Fossils indicate that the coast redwood used to exist into Idaho. Today, Idaho is too dry for this species, and the coast redwood is confined to a fog belt along northern coastal California and southwestern Oregon (i.e., the northwest corner of the California Floristic Province).

Similarly, fossils of Sequoiadendron chaneyi (giant sequioa's direct ancestor) are found in Nevada (part of the Great Basin). It existed there before the collapse of the Miocene plateau, when climate was cooler and more moist. Today, the only remaining species of the genus, Sequoiadendron (once found throughout the northern hemisphere), is giant sequoia. It is only found in pockets in California mountains where water exists close to the soil surface.

Neoendemics are are species that have arisen by speciation events within a geographic region and have never existed outside that geographic region.

The California Floristic Province has many neoendemics because...

1) It's mediterranean climate is found nowhere else in North America and was a novel climate when it developed.

Why is that important?

When the mediterranean climate developed in California, there were no pre-existing species that were well adapted to that climate in North America. It was a new climate that presented new challenges (and new selective forces). Most species that adapted to the new mediterranean climate in California are thought to have descended from species that occupied semi-arid regions of Mexico and the southwestern US (not areas with mediterranean climates). Many California neoendemics are now so different (phenotypically, genetically, and ecologically) from their ancestors that they are considered different species from those ancestors.

This same process occurred in other geographic regions with mediterranean-type climates (Chile, South Africa, southwestern Australia, and the Mediterranean region, itself). Though similar in climate, these regions are widely separated. (They are on different continents.) When the mediterranean climate developed in each of these five regions, the species that adapted to it descended from species that were already on that continent. The result is that each of the five mediterranean regions has its own unique set of endemic species.

Another reason that the California Floristic Province has a lot of neoendemics is because...

2) Its variation in climate and soils, and its mountain ranges, produce conditions that promote evolutionary divergence.

Differing conditions favor different adaptive traits. Therefore, seeds of a species that are widely dispersed to areas with different ecological conditions will establish populations that may experience different selective pressures, favoring individuals with different traits in different locations. This will tend to cause the populations to diverge genetically and phenotypically over time, potentially becoming different species.

Speciation is generally only possible where gene flow between populations is low (even if selection is pushing them apart). Mountain ranges and other topographic features in California often limit gene flow (by limiting pollen flow, pollinator movement, seed dispersal, etc.). This allows divergence and speciation to happen.

As a result, California appears to have a large number of species that evolved here (diverged from ancestral species) and occur nowhere else.

CNPS, Rare Plant Program (2014) Inventory of Rare and Endangered Plants (online edition, v8-02). California Native Plant Society, Sacramento, CA. Website http://www.rareplants.cnps.org [accessed 13 May 2014].

Explanations of the rarity rankings used by CNPS may be found at http://www.rareplants.cnps.org/glossary.html#globalrank

Harrison, S. P. (2013). Plant and Animal Endemism in California. Univ of California Press.

Imada, C. (2012) Hawaiian Native and Naturalized Vascular Plants Checklist (December 2012 update). Bishop Museum Technical Report 60. Bishop Museum, Honolulu, HI.

Jepson Flora Project (B. G. Baldwin, D. J. Keil, S. Markos, B. D. Mishler, R. Patterson, T. J. Rosatti, and D. H. Wilken, eds.) (2015) Jepson eFlora, http://ucjeps.berkeley.edu/IJM.html [accessed on May 8, 2015]

Kartesz, J.T., The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) (2015) Taxonomic Data Center. (http://www.bonap.net/tdc). Chapel Hill, N.C. (accessed 10 May 2015)

Myers, N., Mittermeier, R.A., Mittermeier, C.G., Da Fonseca, G.A. and Kent, J. (2000) Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature, 403(6772): 853-858.

USDA, NRCS. 2015. The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 8 May 2015). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.