Deserts

Deserts occur in areas with low precipitation (lower than is found in mediterranean climate). Temperature can be hot or cold, precipitation can come as snow or rain, and seasonal patterns of precipitation can vary among deserts.

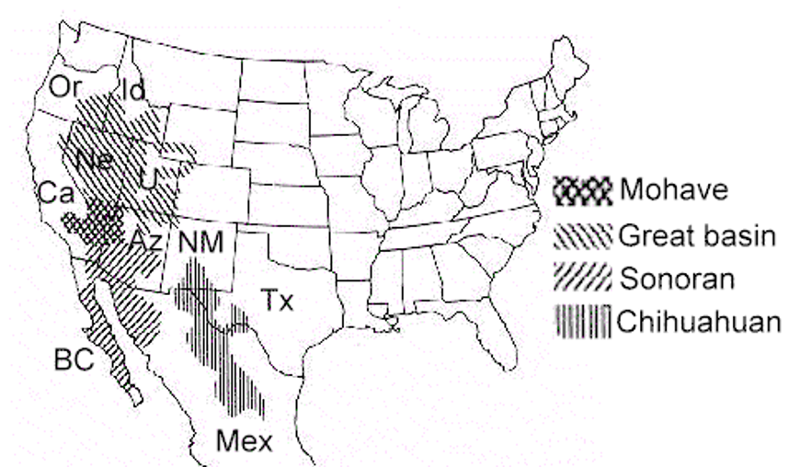

California's transmontane region falls into three different deserts: the Great Basin Desert, the Mojave Desert, and the Sonoran Desert. These deserts differ in temperature and/or precipitation patterns. They also differ in the plant species that dominate them.

The Mojave Desert is the driest desert of California's three deserts. It has dry summers and extreme temperature swings. It is the desert that exists across the mountains to the east of CSUSB.

The Mojave Desert is the driest desert of California's three deserts. It has dry summers and extreme temperature swings. It is the desert that exists across the mountains to the east of CSUSB.

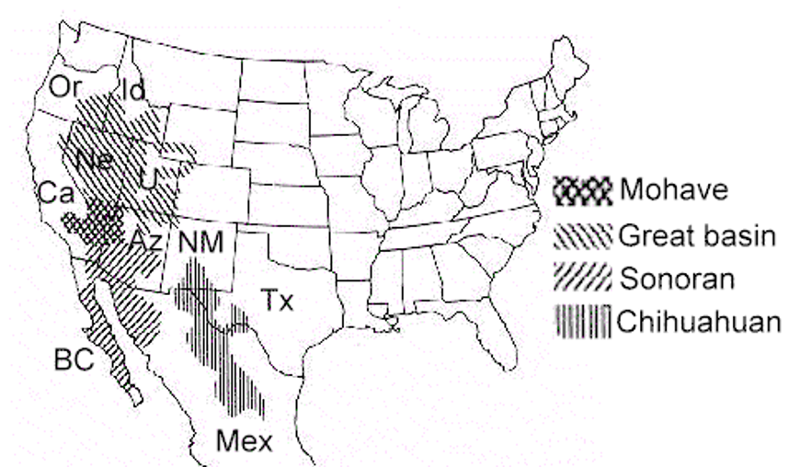

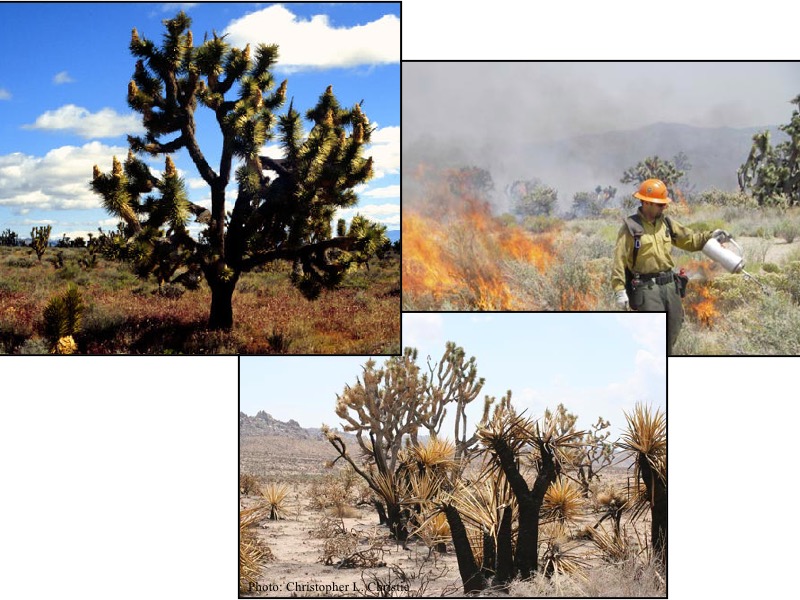

Yucca brevifolia (Joshua tree) is generally considered an indicator species of the Mojave Desert.

The Sonoran Desert lies to the south of the Mojave Desert. It is hotter, on average, than the Mojave Desert, but it is not as dry during the summer. It has a bimodal pattern of rainfall with winter rains and summer thunderstorms.

The giant saguaro cactus (Carnegiea gigantea) is endemic to the Sonoran Desert .

The Great Basin Desert is the coldest desert in California. It exists primarily in Nevada, western Utah, and soutnern Idaho, but it covers small bits of southeastern Oregon and eastern California.

Precipitation in the Great Basin Desert comes primarily in the winter and as snowfall.

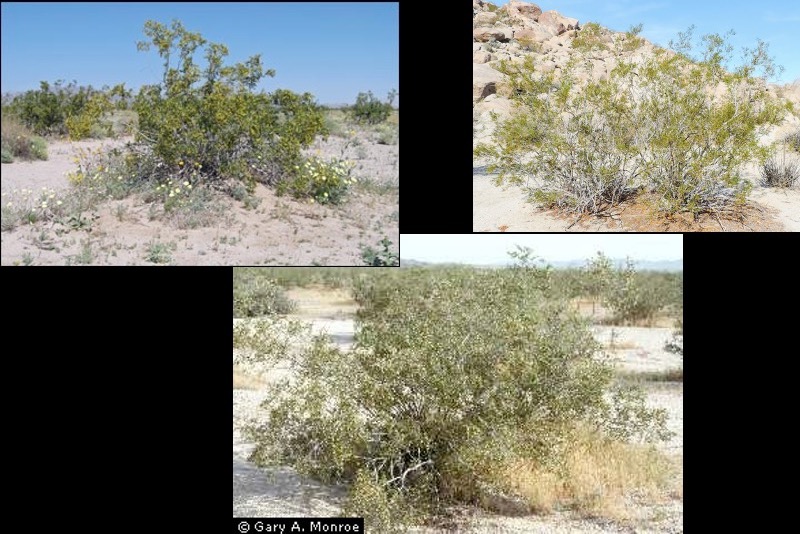

The dominant plant species of the Great Basin Desert is big sagebrush (also known as Great Basin sagebrush), Artemisia tridentata.

There are several ways that different desert plants deal with low water availability.

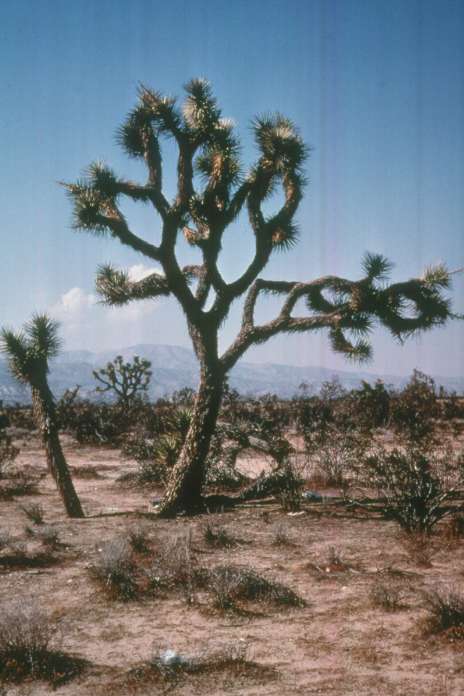

Some plants put down deep roots, reaching a supply of soil water that is more constantly available than surface soil water. These typically have small leaves, reducing transpirational water loss and keeping leaves from heating much above air temperature.

Rather than tapping constant or perennial stores of soil water, some plants specialize in taking up water as quickly as possible after brief rains and storing that water in the plant's body for later use. These are succulent plants, like cacti. Brief rains may only wet a few cm of surface soil, and that water may evaporate from the soil surface in just a day or two. Some cacti produce "rain roots": ephemeral, shallow roots that are produced in response to rainfall and then die. The production of rain roots maximizes water capture from brief rains.

Even the giant saguaro cactus does not have deep roots. It's tap root goes down less than a meter, but it has an extensive network of very shallow roots.

Annual plants also take advantage of rainfall. These must grow and go to seed quickly, completing their life cycle before the soil dries out.

Annual plants also take advantage of rainfall. These must grow and go to seed quickly, completing their life cycle before the soil dries out.

Zones of relatively fertile soil around shrubs in the desert have been called "Fertile Islands". They tend to support more luxurious growth of numerous species, leading to a pattern in which species are clumped together with relatively bare areas between them.

Soil tends to be more fertile under the shrubs for several reasons.

Smaller plants (annuals and others) tend to cluster under shrubs for several reasons.

Salt flats or salt pans can occur in depressions in deserts. Salt accumulates on the surface of the soil. Few plant species can tolerate such a saline environment.

Please read about the factors that cause salt flats to form by following this link.

Salt in the soil is detrimental to plants in two ways:

Plants that can tolerate higher levels of salt in soil may...

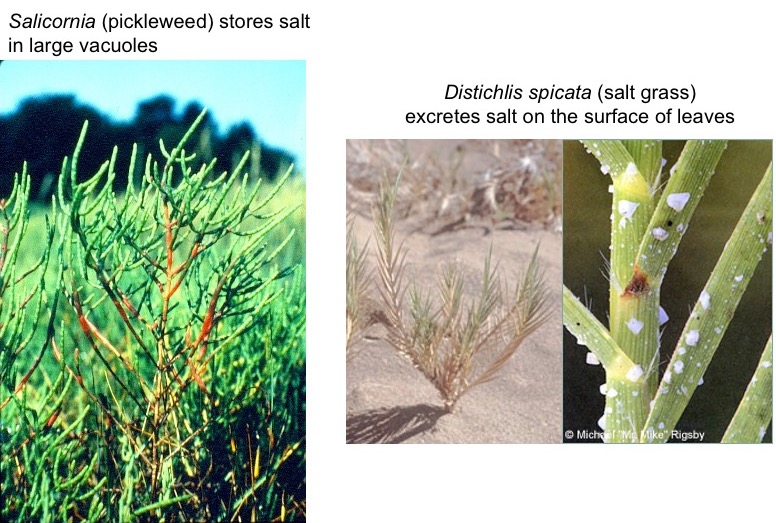

The plants below are found both in salt marshes along the coast and in salty areas of drier inland areas.

Salicornia (pickleweed) has a succulent stem where salt can be stored in vacuoles. Note that the living cells in the older part of the Salicornia, below, are dying (presumably, full of salt).

Distichlis spicata (salt grass) is a species that excretes salt from glands on its leaves. (You can see the dried salt crystals on the plant below.)

Where water comes to the soil surface you often find trees in deserts. Riparian forests of willows, cottonwoods and other trees may be found along creeks and rivers.

Palm oases, near streams and springs in the desert, support California's only native palm species, Washingtonia filifera.

Despite the harsh climate, some non-native species have become invasive in desert systems.

Tamarix spp. (tamarisk or salt-cedar) has been widely planted. It was introduced into the west in the 1800s as a source of wood, shade, and erosion control. Since then, Tamarix species have taken over many riparian areas, displacing the native willows and cottonwoods.

Annual grasses from Europe and Eurasia have colonized large tracks of desert, threatening desert species by promoting fire. Most desert species do not tolerate fire. It is thought that fire was rare in deserts in the past due to the discontinuous fuels. (Bare spaces between shrubs would prevent any fire started by lightening from spreading far.) The presence of the introduced annual grasses provides a thicker, more continuous layer of dead fuels in the desert, helping fire both start and spread.

In the Great Basin, it is cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum) that fills in the interspaces between sagebrush plants. Great Basin sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata) does not tolerate fire, and has been eliminated from large area of the Great Basin by repeated fires.

In the Mojave Desert, it is primarily Bromus rubens (red brome) that has colonized the desert. As noted previously, most desert plants are intolerant of fire. The fire-response of the Joshua tree (Yucca brevifolia), however, is not unclear. In some places, fire appears to completely kill the Joshua tree; in other places Joshua trees have resprouted after fire. The cause of that variation in fire response is not known yet.

Check your understanding: