California's Grasslands

Most originated in the Mediterranean region. There are also many non-native forbs that inhabit California's grasslands and disturbed areas.

There is some debate about what these systems looked like before European contact. They may have been dominated by perennial bunchgrasses, or they many have been dominated by wildflowers.

In years with good spring rainfall, California often experiences prolific wildflower blooms. This may be what more of California looked like before the introduction of the non-native annual grass species.

The introduced annual grasses tend to germinate early in the winter and compete strongly for soil water as the seasonal drought develops through the spring. They cause the top 30-100 cm of soil to dry out very quickly. This often prevents other plant species from establishing or surviving.

Historical accounts of are of limited use in reconstructing the earliest introductions of non-native species in California, because the earliest explorers and European colonists were generally not botanists and non-native plants were introduced and spread before most botanists got to California.

Some historical accounts do refer to vegetation changes. For example, journal writings from the Rancho Period in California (mid-1800s, before the Gold Rush) mention mustard taking over large areas of ranch land.

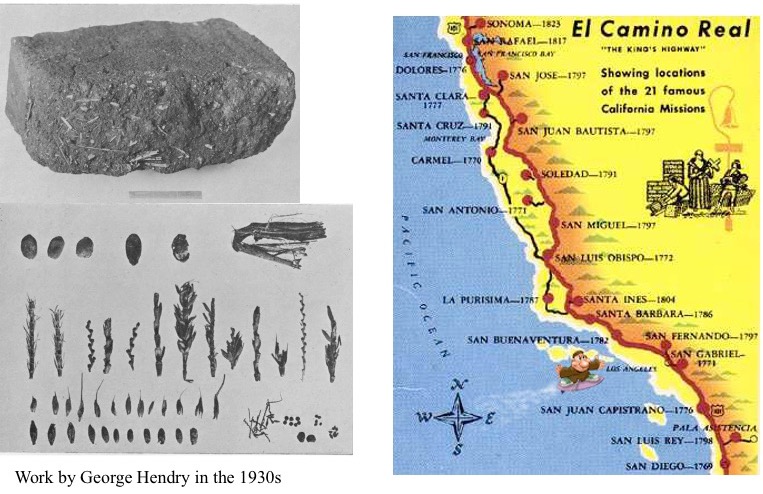

We can get some hints of when species were introduced by using archaeological methods.

Adobe bricks from Spanish missions that were built between the late 1700s and early 1800s give us some information on changing vegetation.

Adobe bricks, being made of mud, tend to contain fragments of whatever is in the local soil where the brick was made. A series of studies in the 1920s and 1930s found that a few European plant species were present in the oldest mission bricks tested. These species, therefore, presumably entered California prior to the mission-building period. A much larger number of non-native species appear in older bricks of the missions, suggesting that those species entered California during the mission-building perio (probably as contaminent in crop seed).

.

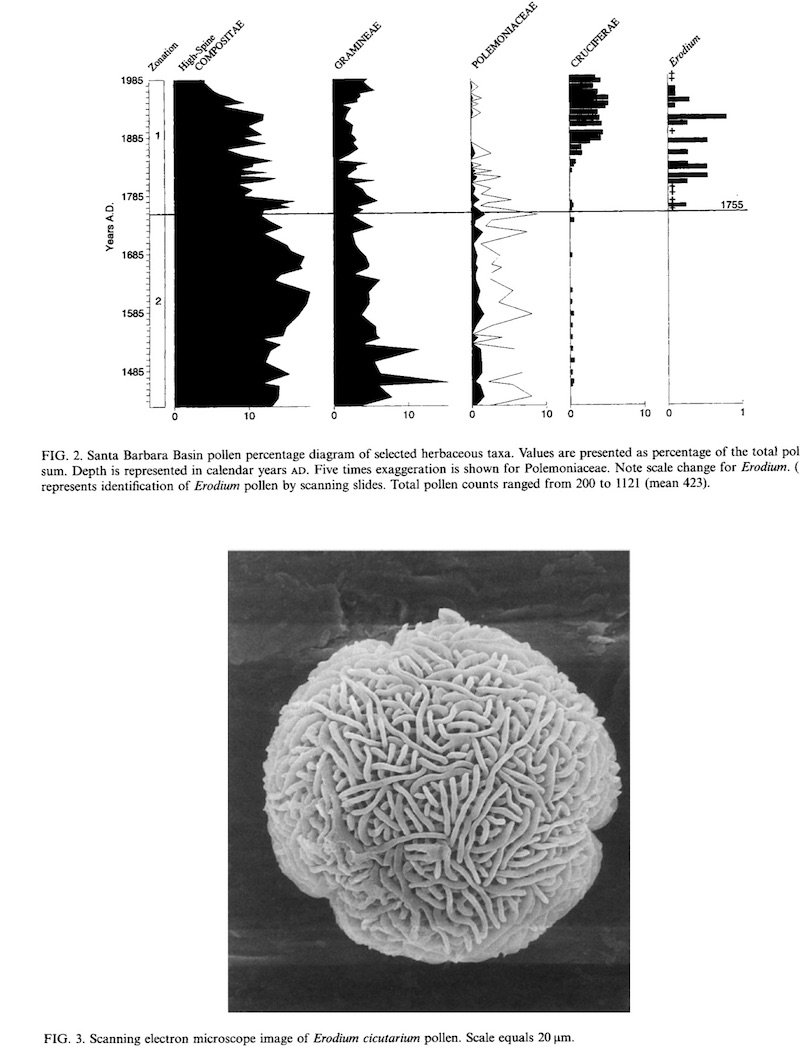

Pollen in sediment cores give us some information. Such cores are taken from areas (usually lakes or other wetlands) where run-off deposits sediments. In such cores, material in the upper layers is most recently deposited, and deeper layers are older. A variety of methods may be used to determine the dates that different layers were deposited.

Sediment cores sea floor in the Santa Barbara Channel have provided a very high resolution record of a number of things (pollen, charcoal, etc.). The figure below (from Mensing and Byrne, 1998) shows pollen from the sunflower family (the Asteraceae, formerly the Compositae), the grass family (the Poaceae, formerly the Gramineae), the Polemoniaceae, the mustard family (the Brassicaceae, formerly the Cruciferae), and Erodium cicutarium, one of the three species identified by Hendry (above) as appearing to have been in California prior to the mission-building period.

The first mission in California was established in 1769. The pollen record below shows that its pollen first appears in the Santa Barbara region around 1755. (The authors speculate that the species moved north from earlier missions in Baja California ahead of the Europeans.) These data appear to confirm Hendry's conclusion that Erodium cicutarium was in California prior to the building of the first missions there.

Check yourself: do you understand the graph above?

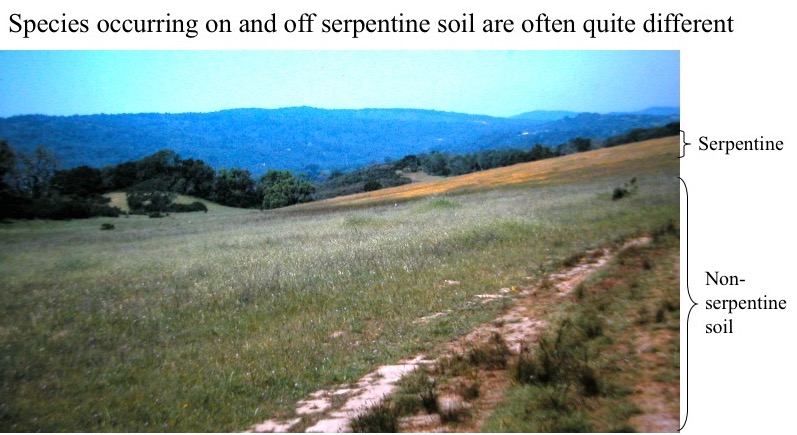

Some edaphic factors may help discourage growth of non-native species, allowing native species to dominate. In grasslands, examples of this include native-dominated grassland patches on serpentine soils and native-dominated plant communities in vernal pools.

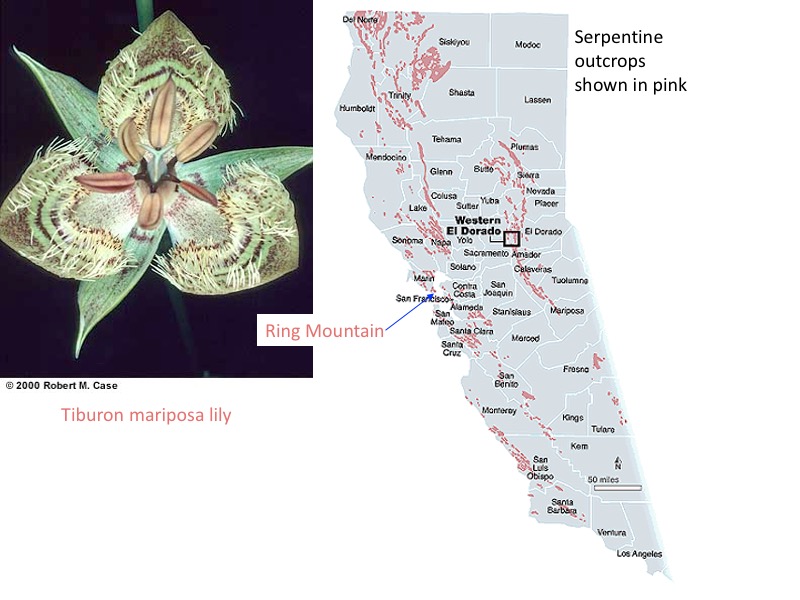

Serpentine soils develop from the weathering of serpentine rock, California's state rock. Serpentine rock forms through metamorphic processes as igneous rock (peridotite) interacts with water in subduction zones. Due to California's large number of geologic faults and subductions zones, California has more than it's fair share of serpentine soil.

Serpentine soil presents numerous challenges to plant growth.

Many plant species that are native to California can tolerate these conditions to some extent. Some are found exclusively on serpentine soil. Introduced species, however, tend to fare poorly on serpentine soil. As a result, competition from introduced species is low on serpentine soil, and serpentine soil tends to...

The image below is of Stanford University's Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve. The yellow band is a band of serpentine soil on which native wildflowers are growing. The green is non-serpentine soils that supports a grassland dominated by introduced annual grasses.

Note: Most plants on serpentine, including serpentine endemics, do better on non-serpentine soil.

They may be restricted to serpentine (or occur more commonly there) because they cannot tolerate competition with the other species occurring off of serpentine.

Some serpentine endemics are very narrowly distributed. One example, Calochortus tiburonensis (Tiburon mariposa lily) is a serpentine endemic that is found only on Ring Mountain in the San Francisco Bay area.

Since serpentine outcrops or groups of serpentine outcrops are widely separated, a species that evolves to tolerate serpentine soil in one locality may not be able to disperse easily to other serpentine areas. This may be the reason we find some serpentine endemics with very narrow geographic distributions.

Vernal pools are places in grasslands where we also find high concentrations of native species. "Vernal" means springtime. Vernal pools are pools that exist during the winter and spring, but dry up later in the spring. They are caused by an impermeable layer under the soil surface that prevents water drainage and causes water to pond.

A complete photo series of seasonal changes of a vernal pool, from winter through the following fall, may be viewed at http://tchester.org/srp/vp/pix/mp_2001.html

Many plants cannot tolerate the environment of a vernal pool.

Species that tolerate the vernal pool environment are ephemeral species. These are annuals that complete their life cycle quickly and go to seed. They typically germinate as waters recede, flower quickly and die. They tolerate the drought and then the early flooding as seed only.

Since different species germinate under slightly different conditions and tolerate slightly different conditions, vernal pool species often flower in rings as the pool dries.

Some plant species are endemic to vernal pools. Some are more widespread natives that simply tolerate vernal pool conditions.

Some species that are endemic to vernal pools have very narrow geographic distributions. For example,

Some species that are endemic to vernal pools have very narrow geographic distributions. For example,

Butte county meadowfoam is endemic to vernal pools of Butte County (only).

San Diego Mesa mint is endemic to vernal pools of San Diego County (only).

Vernal pool endemics are of particular conservation concern because...

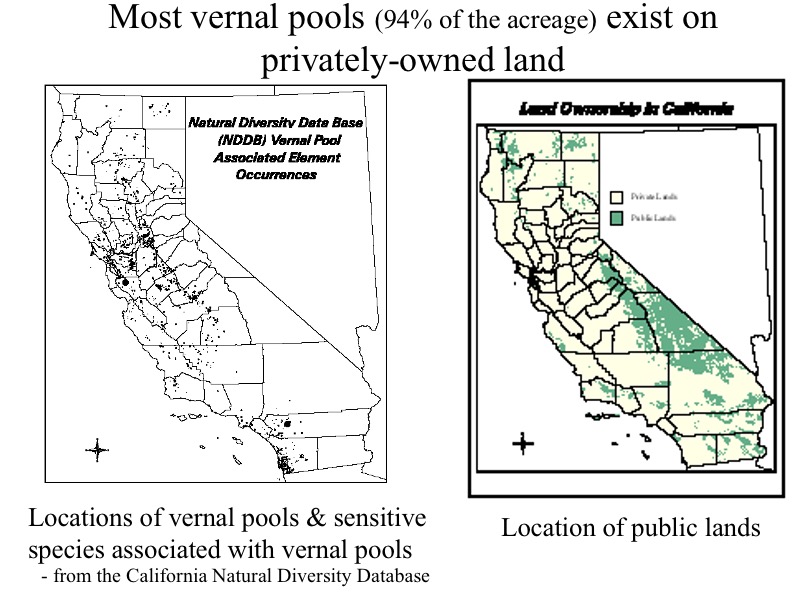

The maps below show the distribution of vernal pools in California and the distribution of public lands. There is very little overlap.