Habitats of Southern California

Due to its wide range of elevations, rock types, and interactions with the ocean, southern California has a range of climates and habitat types.

Climates

Elevation affects temperature: the higher you go on a mountain, the cooler it is. And mountains affect rainfall: as air from the ocean moves across the land and is pushed up a mountain into cooler zones, water vapor in the air condeses and it rains. This leaves the air with less moisture in it as the air moves down the side of the mountain away from the ocean. Thus, the ocean-facing sides of mountains are usually wetter (not wet, but wetter) than the sides away from the ocean. Southern California has three different climate types:

- The part of southern California between the ocean and the major mountain chains (the Sierra Nevada, the Transverse Ranges, and the Peninsular Ranges) has a Mediterranean climate, with hot, dry summers and cool wet winters.

- The part of southern California north and east of the major mountain chains have a desert climate, which is drier than the Mediterranean climate. There are two types of deserts in southern California: the Mojave Desert, which receives what little rain it gets primarily during the winter, and the Sonoran Desert, which is south and east of the Mojave Desert, and receives both winter and summer rainfall.

- The tops of the mountains that receive significant snowfall in the winter also have dry summers. Some refer to them as having a mountain climate.

Vegetation

The map below shows the potential distribution of major vegetation types in the Los Angeles/Inland Empire/Victorville area. The red dot shows the location of California State University, San Bernardino. The higher elevations of the San Gabriel Mountains and the San Bernardino Mountains are covered in forest types, like jeffrey pine forest. On the desert-facing slopes of these mountains, juniper and pinyon pines occur, with various types of desert scrub occuring at lower elevations. On the coastal side of the mountains, chaparral is found below the forests, and coastal sage scrub is found at lower elevations. Very little coastal sage scrub remains today, because most of its former range has been covered by urban development.

A brief description of these different vegetation types, with special emphasis on their response to fire, is given below.

Jeffrey pine and ponderosa pine forests

Jeffrey pines and ponderosa pines are very similar in appearance, Both occur in the the San Gabriel and San Bernardino Mountains. These trees have thick bark that protect them from the heat of low-intensity ground fires when the trees are mature. Historically, frequent fires kept the understory low and open. (The understory consists of the shorter plants below the canopies of the mature trees.) Thick bark protected the mature trees from the resulting low ground fires. Studies of fire scars on trees in the San Bernardino Mountains indicated that these forest stands burned, on average, every 10-12 years before 1905, when the Forest Service and organized fire-suppression efforts began. These same fire scar records indicated that fires became less frequent after 1905, occuring on average, every 22-29 years (McBride and Lavin, 1976), This type of pattern has been observed throughout the western United States. The reduced fire frequency has allowed shrubs and small trees in the understory to grow more thickly, creating a situation in which fires do not remain small and low, but burn up into the tree canopies using the thick shrubs and small trees as "ladder fuels". Mechanical treatments and deliberate, prescribed burns to return these forests to a more open state and keep fires low are now part of forest management in jeffrey pine and ponderosa pine forests.

Jeffrey pines and ponderosa pines are very similar in appearance, Both occur in the the San Gabriel and San Bernardino Mountains. These trees have thick bark that protect them from the heat of low-intensity ground fires when the trees are mature. Historically, frequent fires kept the understory low and open. (The understory consists of the shorter plants below the canopies of the mature trees.) Thick bark protected the mature trees from the resulting low ground fires. Studies of fire scars on trees in the San Bernardino Mountains indicated that these forest stands burned, on average, every 10-12 years before 1905, when the Forest Service and organized fire-suppression efforts began. These same fire scar records indicated that fires became less frequent after 1905, occuring on average, every 22-29 years (McBride and Lavin, 1976), This type of pattern has been observed throughout the western United States. The reduced fire frequency has allowed shrubs and small trees in the understory to grow more thickly, creating a situation in which fires do not remain small and low, but burn up into the tree canopies using the thick shrubs and small trees as "ladder fuels". Mechanical treatments and deliberate, prescribed burns to return these forests to a more open state and keep fires low are now part of forest management in jeffrey pine and ponderosa pine forests.

Piñon pine woodlands (also spelled "pinyon" pine)

Pinyon pine woodlands occur on the desert-

Pinyon pine woodlands occur on the desert- facing slopes of the mountains in southern California. Pinyon pines produce large seeds that are often harvested, shelled, and eaten by humans as "pIne nuts". In contrast to jeffrey pines and ponderosa pines, pinyon pines do not tolerate fire well. Mature pinyon pine trees do not have bark that is thick enough to protect them, and even low-intensity ground fires will kill the trees. Researchers from UC Riverside have estimated that, historically, pinyon pine forests in southern California burned, on average, only once every 480 years. They also estimated that it took 100-150 years for a burned pinyon pine woodland to recover enough to look the way it did before a fire (Wangler and Minnich, 1996). As a result, using prescribed fire is probably not a good way to manage pinyon pine forests if the objective is to keep the pinyon pine forest healthy.

facing slopes of the mountains in southern California. Pinyon pines produce large seeds that are often harvested, shelled, and eaten by humans as "pIne nuts". In contrast to jeffrey pines and ponderosa pines, pinyon pines do not tolerate fire well. Mature pinyon pine trees do not have bark that is thick enough to protect them, and even low-intensity ground fires will kill the trees. Researchers from UC Riverside have estimated that, historically, pinyon pine forests in southern California burned, on average, only once every 480 years. They also estimated that it took 100-150 years for a burned pinyon pine woodland to recover enough to look the way it did before a fire (Wangler and Minnich, 1996). As a result, using prescribed fire is probably not a good way to manage pinyon pine forests if the objective is to keep the pinyon pine forest healthy.

Desert

The desert shown on the map above is the Mojave Desert, dominated by creosote bush and Joshua trees. The Mojave Desert receives less summer rain than the Sonoran Desert which lies to the southeast of the Mojave Desert and contains the large columar cacti that most people think of when they think of deserts. In the Mojave Desert, low shrubs and cacti occur may occur among the creosote bushes and Joshua trees. In wet years, ephemeral annual wildflowers may carpet the open spaces between shrubs. These ephemerals (meaning "lasting a short time") germinate, grow quickly, flower, and produce seed during the short periods that water is available near the surface of the soil.

The dominants of the Mojave Desert are long-lived and have

The dominants of the Mojave Desert are long-lived and have  interesting pollination characteristics. Joshua trees (left) are generally restricted to the Mojave Desert and can live to be several hundred years old. They are pollinated by only two types of yucca moths that lay their eggs in the ovary of a flower, then deposit a ball of pollen on the stigma of the pistil. Pollination ensures that seeds develop in the ovary, and seed development ensures that the moth larvae have something to each when they hatch. (This only benefits the plant if the larvae do not eat all the seeds.) Creosote bush (right), which is more widely distributed than the Joshua tree, may fragment and produce clones of bushes as the plants age. The oldest clone known exists in Lucerne Valley, California, and is estimated to be over 11,000 years old. The yellow petals of the flowers of creosote bush are reported to twist 90 degrees after the flower has been pollinated. Information on these two species may be found in many sources on the web, including the US Forest Service's Fire Ecology Information System (http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/) and the University of Arizona Arboretum website (http://apps.cals.arizona.edu/arboretum/taxon.aspx?id=36).

interesting pollination characteristics. Joshua trees (left) are generally restricted to the Mojave Desert and can live to be several hundred years old. They are pollinated by only two types of yucca moths that lay their eggs in the ovary of a flower, then deposit a ball of pollen on the stigma of the pistil. Pollination ensures that seeds develop in the ovary, and seed development ensures that the moth larvae have something to each when they hatch. (This only benefits the plant if the larvae do not eat all the seeds.) Creosote bush (right), which is more widely distributed than the Joshua tree, may fragment and produce clones of bushes as the plants age. The oldest clone known exists in Lucerne Valley, California, and is estimated to be over 11,000 years old. The yellow petals of the flowers of creosote bush are reported to twist 90 degrees after the flower has been pollinated. Information on these two species may be found in many sources on the web, including the US Forest Service's Fire Ecology Information System (http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/) and the University of Arizona Arboretum website (http://apps.cals.arizona.edu/arboretum/taxon.aspx?id=36).

In undisturbed desert, there are often large spaces between shrubs. This does not mean the shrubs are not competing with each other. For many desert shrubs, most of the the plant's body is below ground. There can be strong competiton between the roots of desert plants for water and other soil resources, even if it looks like the shrubs are widely spaced. We see only a small part of the plant: the aboveground part.

Like the pinyon pines, few desert plants can tolerate fire. In the past, large openings between desert shrubs kept fires from spreading and burning large areas. Today, non-native annuals like red brome grass (from Europe) have colonized large areas of the desert, creating continuous carpets of fine fuels that carry fire and have resulted in more frequent fire. In recent years, non-native annuals in the mustard family have followed the non-native grasses into the desert, spreading along roads and colonizing disturbed areas. These invasive, non-native plants are considered to be among the worst threats to the native desert vegetation because they both compete with the native desert plants and promote fire.

|

Intact desert vegetation near Phelan, CA |

Disturbed desert site, colonized by tumble mustard (Sisymbrium altissimum, from Europe) |

Chaparral

Chaparral vegetation is dominated by evergreen, sclerophyllous ("hard-leaved") shrubs. The image to the left shows a disturbed opening in mature chaparral, which covers the hillsides in the background.

Chaparral vegetation is dominated by evergreen, sclerophyllous ("hard-leaved") shrubs. The image to the left shows a disturbed opening in mature chaparral, which covers the hillsides in the background.

Different plant species have different ways of recoving from fire. Some shrub species resprout from root crowns or rhizomes after fire. Some are killed by fire and have seeds in a seedbank that are stimulated to germinate following fire. Geophytes (plants with underground storage organs that die back to the ground each summer), simply regrow from their underground storage organs. Annual plants are rare in mature chaparral, being found only in openings. However, many have seeds that are stimulated to germinate by heat or smoke, and wildflowers may carpet the area the spring after a fire. Seeds of these fire-followers may remain dormant in the soil for 50 years or more, existing only in the seedbank between fires, and germinating to produced flowering plants after a fire.

Although chaparral vegetation is adapted to fire, fires that are too frequent can eliminate chaparral species. If a resprouting species is reburned 1-2 years after a fire, it may be unable to resprout again: it depletes its starch reserves in the root by producing new shoots after the first fire, then does not have time to build up enough starch reserves between fires to successfully resprout again. If an "obligate seeder" is burned, it will be eliminated from a site if a second fire occurs before the plants germinate, grow, mature and set seed. An obligate seeder is a species that dies in a fire and has seeds in a soil seed bank that are stimulated to germinate by smoke or heat. A fire will kill existing plants and stimulate germination. The germination will deplete the soil seed bank. No new seeds will be added to the soil seed bank until the seedlings grow into mature plants that flower and produce seeds. The species that are most vulnerable to a short fire-return interval (time between fires) are the obligate seeders that grow slowly and take many years to reach maturity and produce many seeds.

Most chaparral species can persist in areas where fire occurs once every 20-80 years. Some species can tolerate more frequent fires, but not all species.

|

Wild cucumber has a large storage root. It dies back to the ground each summer and a new shoot emerges with the first rains. It is usually not damaged at all by fires. |

Toyon and many other species will resprout from root crowns |

Hoary-leaved ceanothus is an obligate seeder. It dies in a fire. It takes 8-10 years to reach maturity and longer to get big enough to produce enough seed to replenish the soil seed bank. |

Annual fire-followers, stimulated to germinate by fire, may bloom profusely in the 1-2 years after a fire. |

Coastal sage scrub

Coastal sage scrub, like chaparral, is dominated by shrubs. The dominant shrubs of coastal sage scrub, though, are more shallowly rooted than those of chaparral, and most are drought-deciduous. (These traits are related: shallowly rooted shrubs do not have access to deep soil water, so they can't supply water to their leaves all summer. Therefore, they just drop most of them.) Leaves of these shrubs are flexible, not hard and durable like the leaves of the chaparral dominants. For this reason, coastal sage scrub is sometimes called "soft chaparral".

Dominant shrubs of coastal sage scrub include members of the mint family (black sage, white sage, purple sage, etc.) and California sagebrush. They tend to be shorter than shrubs of hard chaparral and mature more quickly, most maturing within four years. Therefore, although most of these shrubs are killed by fire, they can complete their life cycle in just a few years, and withstand more frequent fires than many species of hard chaparral. Fires that occur more frequently than once every four years, however, will tend to eliminate these shrubs, converting the site to an annual grassland.s

|

March 2002 (Before the fire) |

December 2003 (photo: David Neighbours) |

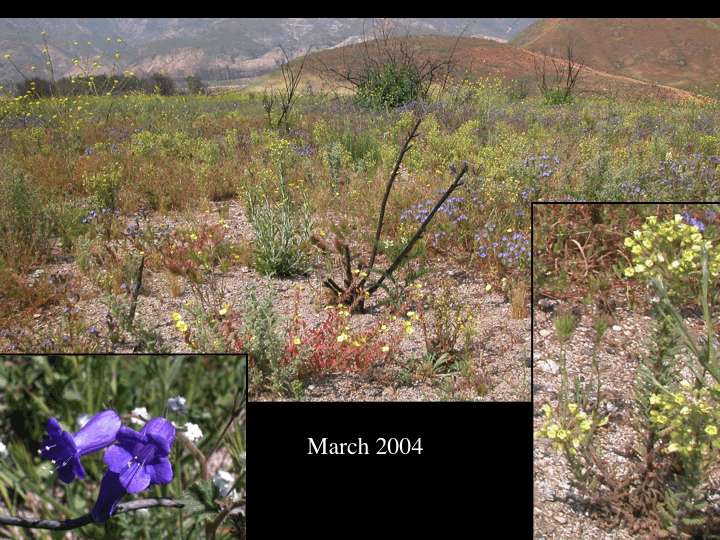

March 2004 (5 months after fire)

|

May 2005 (Second spring after fire) |

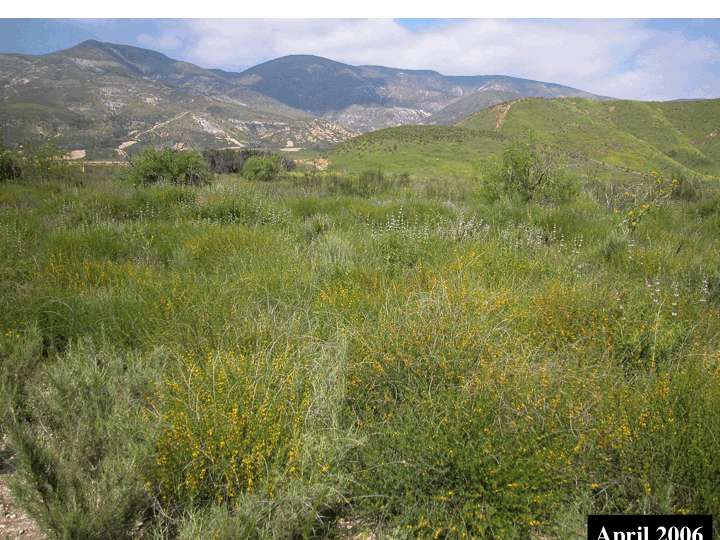

April 2006 (Third spring after fire) |

Annual grasslands

Annual grasslands in California are dominated by non-native annual grasses that have been introduced into California since Europeans arrived. Most of these introductions were probably accidental. There is some debate about what grasslands of California actually looked like before these introduced grasses took over. Some people think they were dominated by native perennial grasses; others think they were dominated by native wildflowers, like the California poppy.

Today, annual grasses tend to replace native plant communities where frequent fire, mechanical disturbance, or other disturbances eliminate the native vegetation. These grasses grow early in the spring and use up water in the upper soil layers. This makes it difficult for seedlings of other species (including shrub, tree, and wildflower seedlings) to survive. The grasses outcompete them for water. Furthermore, these grasses die relatively early in the season, providing fine fuels that ignite easily and promote frequent fires. As noted above, frequent fires will eliminate many native species, leaving the grasses to dominate the site.

Today, annual grasses tend to replace native plant communities where frequent fire, mechanical disturbance, or other disturbances eliminate the native vegetation. These grasses grow early in the spring and use up water in the upper soil layers. This makes it difficult for seedlings of other species (including shrub, tree, and wildflower seedlings) to survive. The grasses outcompete them for water. Furthermore, these grasses die relatively early in the season, providing fine fuels that ignite easily and promote frequent fires. As noted above, frequent fires will eliminate many native species, leaving the grasses to dominate the site.

Check your understanding:

References

McBride, J. R., & Laven, R. D. (1976). Scars as an indicator of fire frequency in the San Bernardino Mountains, California. Journal of Forestry, 74(7), 439-442.

Wangler, M. J. & Minnich, R. A. (1996). Fires and succesion in pinyon-juniper woodlands of the San Bernardino Mountains, California. Madroño, 43(4), 493-514.