Taxonomy and Nomenclature

Taxonomy and Nomenclature

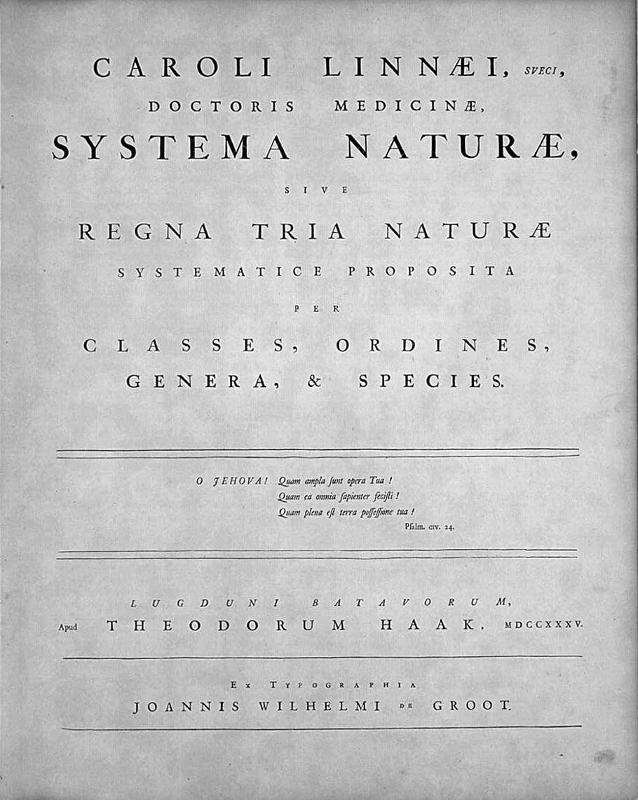

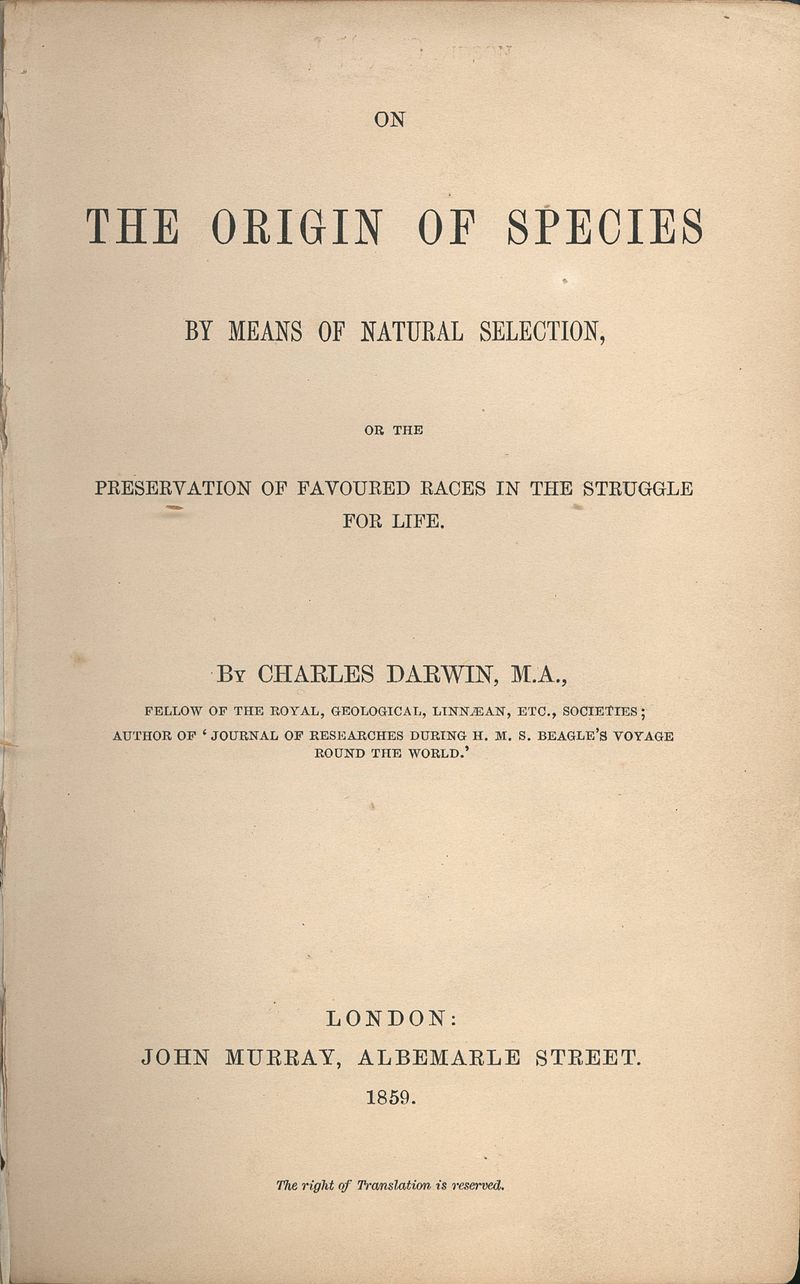

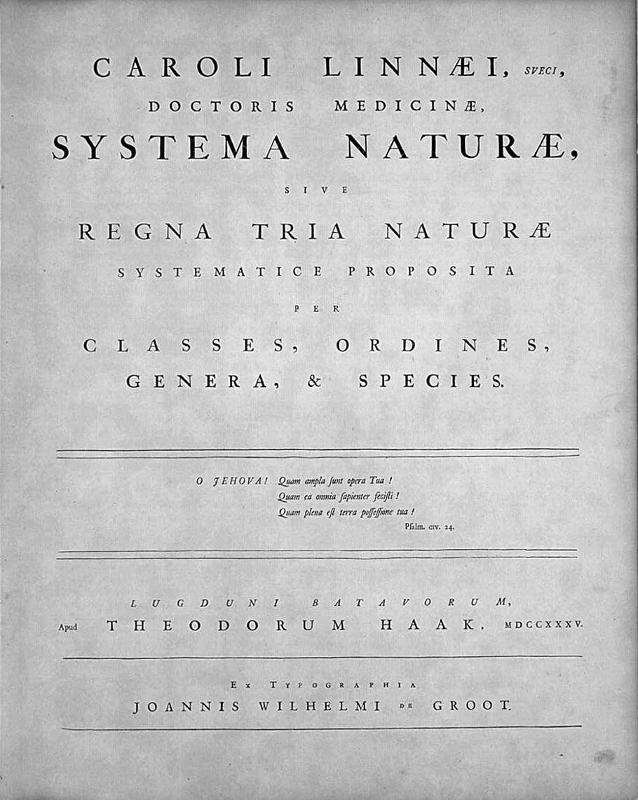

Today, the naming and classification of plants is based on our understanding of their evolutionary and genetic relationships. Although these concepts are inherently linked today, systems for naming and classifying organisms were developed before our understanding of evolution developed. The hierarchical system we use for naming and classifying organisms is based on that of Carl Linnaeus (Swedish botanist, zoologist, and physician) and his publication, Systema Naturae, published in 1735. Our understanding of evolution is usually traced to Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species, published more than one hundred years later, in 1859.

Today, the naming and classification of plants is based on our understanding of their evolutionary and genetic relationships. Although these concepts are inherently linked today, systems for naming and classifying organisms were developed before our understanding of evolution developed. The hierarchical system we use for naming and classifying organisms is based on that of Carl Linnaeus (Swedish botanist, zoologist, and physician) and his publication, Systema Naturae, published in 1735. Our understanding of evolution is usually traced to Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species, published more than one hundred years later, in 1859.

As our understanding of genetic relationships and evolutionary processes has improved, we have come to expect taxonomy to reflect genetic or evolutionary relationships, rather than some arbitrary system of grouping organisms. Michener et al. (1970) explained the relationship of "taxonomy" to a broader field of "systematics" (which includes evolutionary biology) as follows:

"Systematic biology (hereafter called simply systematics) is the field that (a) provides scientific names for organisms, (b) describes them, (c) preserves collections of them, (d) provides classifications for the organisms, keys for their identification, and data on their distributions, (e) investigates their evolutionary histories, and (f) considers their environmental adaptations. This is a field with a long history that in recent years has experienced a notable renaissance, principally with respect to theoretical content. Part of the theoretical material has to do with evolutionary areas (topics e and f above), the rest relates especially to the problem of classification. Taxonomy is that part of Systematics concerned with topics (a) to (d) above."

Phylogeny describes the evolutionary history and relationships of various groups of organisms.

One of the reasons you need to understand the role of systematics in the classification and naming of plants today is that, as our understanding of phylogenetic relationships change, the names of plants can change, they can be put into different genera, genera may be split and put into different families, etc.

Reference: Michener, Charles D., John O. Corliss, Richard S. Cowan, Peter H. Raven, Curtis W. Sabrosky, Donald S. Squires, and G. W. Wharton (1970). Systematics In Support of Biological Research. Division of Biology and Agriculture, National Research Council. Washington, D.C. 25 pp.

Hierarchical classification

The hierachical classification system we use for classifying organisms has several levels. Closely related species are grouped into a genus; closely related genera are grouped into a family, etc. From the broadest grouping down to the smallest, most specific groups, those levels include:

Kingdom: Plantae

Phylum (or Division) (e.g., Anthophyta (=angiosperms), one of several phyla in the Kingdom Plantae)

Class (e.g., Magnoliopsida (=dicots), one of the classes in the phylum, Anthophyta)

Order (e.g., Asterales, one of several orders in the class, Magnoliopsida)

Family (e.g., Asteraceae, one of several families in the order, Asterales)

Genus (e.g., Rafinesquia, one of several genera in the family, Asteraceae)

Species (e.g, Rafinesquia californica, one of two species in the genus, Rafinesquia)

[Sometimes an infraspecific taxonomic level, such as subspecies or variety]

The Jepson manual groups plants into eight major monophyletic groups or clades that reflect the most recent classification systems of vascular plants. It is illustrated here. All of these plants have a common ancestor, but the Lycophytes (seedless vascular plants with one sporangium per leaf) diverged from other plant groups the earliest. Next, the common ancestor of seed plants diverged from the ferns (seedless vascular plants with sporangia arranged in sori on their leaves). Among the seed plants, the common ancestor of flowering plants diverged from the gymnosperms, then various groups of angiosperms (flowering plants) continued to diverge. You can click on the original version of the cladogram on the Jepson Manual website to see finer-scale phylogenetic relationships (e.g., all of the families of gymnosperms, all of the genera in one family in the gymnosperms, etc.). Follow this link: https://ucjeps.berkeley.edu/eflora/clademap/

The Jepson manual groups plants into eight major monophyletic groups or clades that reflect the most recent classification systems of vascular plants. It is illustrated here. All of these plants have a common ancestor, but the Lycophytes (seedless vascular plants with one sporangium per leaf) diverged from other plant groups the earliest. Next, the common ancestor of seed plants diverged from the ferns (seedless vascular plants with sporangia arranged in sori on their leaves). Among the seed plants, the common ancestor of flowering plants diverged from the gymnosperms, then various groups of angiosperms (flowering plants) continued to diverge. You can click on the original version of the cladogram on the Jepson Manual website to see finer-scale phylogenetic relationships (e.g., all of the families of gymnosperms, all of the genera in one family in the gymnosperms, etc.). Follow this link: https://ucjeps.berkeley.edu/eflora/clademap/

Nomenclature (the assigning of names):

There are rules and conventions for choosing and writing names at different taxonomic levels.

The taxonomic levels we will be emphasizing in this class include:

Family

You will be learning to recognize approximately 24 families of plants in this class by their characteristics.

In writing the name of a family (e.g., Asteraceae), note that

- the family name is capitalized

- a family name ends in "-aceae"

- Usually, the family is named for a genus in it (in this case, the genus Aster)

Genus

A genus name is capitalized and italicized. Example: Rafinesquia

Species

|

A short and incomplete history of the binomial

|

|

Gaspard Bauhin (1560-1624) introduced a method of classifying and naming plants that resembles the binomial: a genus name followed by a one- to few-word phrase describing a particular species in the genus.

Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) was the champion of the binomial system. With the publication of his work Species Plantarum in 1753, he gave binomial names to every plant species known at the time and grouped them into genera.

|

A species name is a binomial: it includes both the genus name and a "specific epithet".

The full species name includes the authority or author (the standardized abbreviation of the name of the botanist who originally described it), in addition to the binomial.

Example:

The full name of Rafinesquia californica is Rafinesquia californica Nutt.

- The genus is capitalized and italicized

- The specific epithet is italicized, but NOT capitalized

- "Nutt." refers to William Nuttall, the botanist who described the species in the 1800s. The author is not italicized.

(Wikipedia maintains a long list of standardized abbreviations of authors: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_botanists_by_author_abbreviation_(A) )

In speaking, people generally do not include the authority. They will just say "Rafinesquia californica".

In writing for publication, the authority is included in the name the first time the species is mentioned. After that, it is left off and the genus may be abbreviated to an initial (e.g., R. californica). [Note that if you are writing about both Rafinesquia californica and Rosa californica, you can't abbreviate the genus without causing mass confusion.]

You can never refer to a species by just its specific epithet. Why? Go to the Calflora website (www.calflora.org - ignore the box that asks you to log in). This is a site the compiles information on California plants from many different sources. Search for "californica" in the "plant name" box. How many plants have the specific epithet "californica"? You cannot use "californica" by itself as the species name and expect anyone to know what plant you are talking about.

Origins of names

The binomial (genus and specific epithet) is often referred to as the scientific name or Latin name of a species. Plants also have common names (more on that later). The Latin name is important for communication of scientists from around the world who speak different languages or dialects.

Generic names (Latin or Latinized nouns with first letter capitalized) may be:

- Aboriginal in origin (example: Quercus = oaks)

- Can be named for a person (Herschfeldia for Hirschfeldt)

Specific epithets are usually adjectives that agree in gender with the generic name. They are not capitalized. Types of specific epithets include:

- Aborginal: Aesculus hippocastanum from the Greek "hippos" for horse (in this case, horse chestnut)

- Descriptive: Acer rubrum - from the Latin "rubra", meaning red in color

- Impression: Lonicera fragrantissima - fragrant

- Resemblance : Cercocarpus betuloides - looks like a beech. ("Betula" is the the genus of beech trees.)

- Ecological: Colinsia verna - from the Latin "vernus" meaning 'of the spring' (it blooms in spring)

- Economic: Lycopersicum esculentum - "esculentum" means edible

- Named after a person:

- Quercus engelmannii (Engelmann oak), named after George Engelmann (physician & botanist)

- Amsinckia eastwoodiae ( Eastwood's fiddleneck), named for Alice Eastwood, botanical curator for the California Academy of Sciences in the late 1800s and early 1900s

Michael L. Charters has compiled an excellent online reference for the meaning and origins of California plant names: http://www.calflora.net/botanicalnames/

The process of naming plants

To name a new plant taxon (a species or subspecies), a researcher must

- publish a description of it in a scientific journal or other recognized outlet, and

- designate a "type specimen", which is a preserved specimen that is deposited in a recognized herbarium. This type specimen serves as the primary reference for the new species or subspecies that is being described.

Names must follow the International Code of Nomenclature (formerly, the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature). This code was first established at the 1905 meeting of the International Botanical Congress. Its purpose was to standardize the names of plants. It is revisited and revised every 6 years with recommended changes being published in the journal Taxon.

A couple of the rules in the International Code of Nomenclature are that:

- Scientific names of taxonomic groups are treated as Latin regardless of their derivation.

- The nomenclature of a taxonomic group is based upon priority of publication. (This means that if two researchers try to name the same group different things, the first name published is the correct name. Also, if a name is accidentally applied to two different groups, the first group published gets to keep the name.)

Revising a species' classification and name

Taxonomists do revise plant classification (usually based on new information). Then they have to rename some of the plant groups that are affected. In renaming plants...

- The first published name takes precedence (in cases where some group of plants has to give up its name)

- As much of the previous name is preserved as possible

- The author who first described the group remains as part of the name in parentheses. (The author who is renaming the group becomes the new author, whose name is outside the parentheses.

Example: Diplacus aurantiacus (Curtis) Jeps. is the scientific name for orange bush monkey flower (a.k.a sticky monkey). Interpreting this name, you see that Curtis (William Curtis, 1746-1799) originally described the species. (He had named the species Mimulus aurantiacus, but you can't tell that by looking at the name.) You can see that Jepson (Willis Linn Jepson, 1867-1946) came along later, revised the classification of this species and renamed it.

Example: Diplacus aurantiacus (Curtis) Jeps. is the scientific name for orange bush monkey flower (a.k.a sticky monkey). Interpreting this name, you see that Curtis (William Curtis, 1746-1799) originally described the species. (He had named the species Mimulus aurantiacus, but you can't tell that by looking at the name.) You can see that Jepson (Willis Linn Jepson, 1867-1946) came along later, revised the classification of this species and renamed it.

Another example:

In 1842, John Claudius Loudon described Lodgepole pine and named it Pinus contorta. The official name was Pinus contorta Loudon.

In 1868, Filippo Parlatore described Bolander pine and named it Pinus bolanderi. The official name was Pinus bolanderi Parl.

In 1957, Willian Burke Critchfield examined these (and other) pine species and concluded that these two belonged in the same species and should be considered subspecies.

- Pinus contorta became Pinus contorta Loudon ssp. contorta...(No real change in author. The species took the name Pinus contorta, rather than Pinus bolanderi because P. contorta was the first name published)

- Pinus bolanderi became Pinus contorta Loudon ssp. bolanderi (Parl.) Critchf. ...("bolanderi" remained part of the name, to retain as much of the name as possible. However, it was demoted to the subspecific epithet. Parlatore's name got to stay in the name, because he first described the group. Critchfield puts his name as the author, because he reclassified the species and gave it a new name.

Note that if someone comes along after Critchfield and reclassifies Bolander Pine again, Critchfield's name just gets dropped. The only two groups of authors in a revised name are (1) the author(s) that initially described the group, and (2) the author(s) that have published the current revision and the current name.

Common names vs. Latin names

Common names and Latin names have different benefits and drawbacks.

Common Names:

Benefits:

- Common names are usually easy to spell, pronounce and remember.

- Many people only know and use common names.

Drawbacks:

- A plant may have more than one common name.

- A common name may be used for more than one species.

- A common name of a plant may differ in different places.

Example: In Australia, "Flannel bush" refers to a species in the nightshade family (Solanaceae); in the USA "Flannel bush" refers to a species in the hibiscus family (Malvaceae).

Scientific or Latin Names:

Benefits:

- There is only one correct scientific name for a plant.

- The scientific name is the same name all over the world.

- The scientific name selection follows official rules.

Drawbacks:

Drawbacks:

- Scientific names can be (and often are) officially changed.

- The scientific name is often difficult to spell, pronounce and remember.

Example: Ten years ago, students in this class learned that the Latin name for California suncup (or...one of two species known as California suncup) was Cammisonia bistorta (Torr. & A. Gray) Raven. Due to taxonomic revisions, its accepted name is now Camissoniopsis bistorta (Torr. & A. Gray) W.L. Wagner & Hoch.

Today, the naming and classification of plants is based on our understanding of their evolutionary and genetic relationships. Although these concepts are inherently linked today, systems for naming and classifying organisms were developed before our understanding of evolution developed. The hierarchical system we use for naming and classifying organisms is based on that of Carl Linnaeus (Swedish botanist, zoologist, and physician) and his publication, Systema Naturae, published in 1735. Our understanding of evolution is usually traced to Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species, published more than one hundred years later, in 1859.

Today, the naming and classification of plants is based on our understanding of their evolutionary and genetic relationships. Although these concepts are inherently linked today, systems for naming and classifying organisms were developed before our understanding of evolution developed. The hierarchical system we use for naming and classifying organisms is based on that of Carl Linnaeus (Swedish botanist, zoologist, and physician) and his publication, Systema Naturae, published in 1735. Our understanding of evolution is usually traced to Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species, published more than one hundred years later, in 1859.

The Jepson manual groups plants into eight major monophyletic groups or clades that reflect the most recent classification systems of vascular plants. It is illustrated here. All of these plants have a common ancestor, but the Lycophytes (seedless vascular plants with one sporangium per leaf) diverged from other plant groups the earliest. Next, the common ancestor of seed plants diverged from the ferns (seedless vascular plants with sporangia arranged in sori on their leaves). Among the seed plants, the common ancestor of flowering plants diverged from the gymnosperms, then various groups of angiosperms (flowering plants) continued to diverge. You can click on the original version of the cladogram on the Jepson Manual website to see finer-scale phylogenetic relationships (e.g., all of the families of gymnosperms, all of the genera in one family in the gymnosperms, etc.). Follow this link: https://ucjeps.berkeley.edu/eflora/clademap/

The Jepson manual groups plants into eight major monophyletic groups or clades that reflect the most recent classification systems of vascular plants. It is illustrated here. All of these plants have a common ancestor, but the Lycophytes (seedless vascular plants with one sporangium per leaf) diverged from other plant groups the earliest. Next, the common ancestor of seed plants diverged from the ferns (seedless vascular plants with sporangia arranged in sori on their leaves). Among the seed plants, the common ancestor of flowering plants diverged from the gymnosperms, then various groups of angiosperms (flowering plants) continued to diverge. You can click on the original version of the cladogram on the Jepson Manual website to see finer-scale phylogenetic relationships (e.g., all of the families of gymnosperms, all of the genera in one family in the gymnosperms, etc.). Follow this link: https://ucjeps.berkeley.edu/eflora/clademap/ Example: Diplacus aurantiacus (Curtis) Jeps. is the scientific name for orange bush monkey flower (a.k.a sticky monkey). Interpreting this name, you see that Curtis (William Curtis, 1746-1799) originally described the species. (He had named the species Mimulus aurantiacus, but you can't tell that by looking at the name.) You can see that Jepson (Willis Linn Jepson, 1867-1946) came along later, revised the classification of this species and renamed it.

Example: Diplacus aurantiacus (Curtis) Jeps. is the scientific name for orange bush monkey flower (a.k.a sticky monkey). Interpreting this name, you see that Curtis (William Curtis, 1746-1799) originally described the species. (He had named the species Mimulus aurantiacus, but you can't tell that by looking at the name.) You can see that Jepson (Willis Linn Jepson, 1867-1946) came along later, revised the classification of this species and renamed it.

Drawbacks:

Drawbacks: