Plant characteristics

Dealing with snow

Abrasion from blowing ice crystals can severely damage plant tissue and kill it.

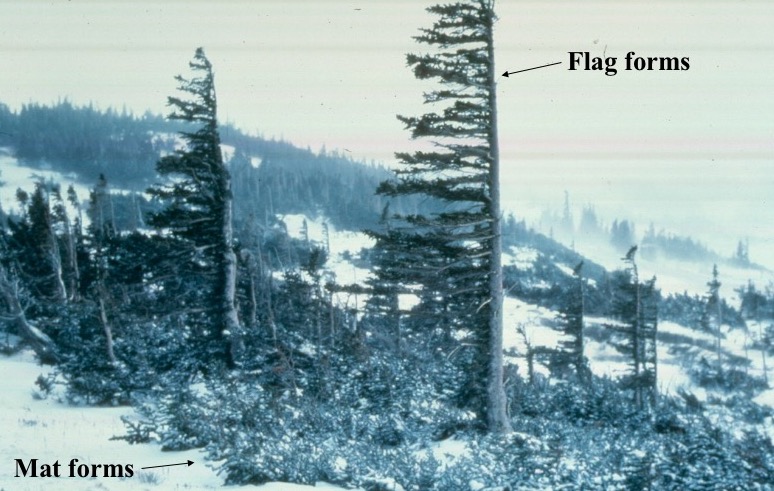

Plants that are covered by a blanket of snow during winter are protected from this type of damage. In very high elevations, where vegetation is sparse and blowing ice crystals are a real hazard, most plants are short. Cushion plants and mat-like plants (below) have two advantages over taller plants:

- They are covered by snow and protected from wind-blown ice crystals during the winter.

- The are in a warmer micro-environment early in spring. After snow-melt in spring, the ground will absorb solar radiation and heat, heating the air right above it. The air near the ground will be warmer during the daytime than air farther from that ground. By remaining short, these cushion plants and mat-like plants live in a micro-environment that warms earlier in the spring. (They are growing in the boundary layer of the ground.) This allows them to begin growing earlier in the year.

At the upper limit of forests (tree line), wind-blown ice crystals damage and shape the trees. This vegetation is known as Krummholz vegetation. Abrasion by blowing snow and ice kills buds, either pruning the tree into a mat-like form or killing buds only on the windward side of the tree to produce a "flag" form.

Snow load can also damage plants. Trees in snowy areas tend to be flexible to shed snow without breaking. Some trees are winter deciduous, and present less surface area to catch snow. Others, however, like the dominant, evergreen gymnosperms, just have to be flexible. They typically have flexible branches and tough needles that can resist damage by ice crystals and droop to shed snow.

In California, heavy snow that extends to lower elevations than normal can severely tree species that are not adapted to it. For example, blue oaks and valley oaks of the foothill woodlands tend to break: their rigid branches do not shed snow easily.

Dealing with nutrient-poor soil

Nutrient-poor conditions tend to select for plants who retain their leaves for a long time. This is because, although plants tend to withdraw a large fraction of the phosphorus, nitrogen, and other nutrients from their leaves before the leaves are dropped, they can never recover all of it. Therefore, every time a plant drops a leaf, it loses nutrients. In a nutrient-poor environment, it is difficult to replace those lost nutrients.

One way to conserve nutrients is to retain leaves for a long time, maximizing the amount of photosynthesis the plant gets out of its investment in individual leaves. It is thought that this is the main reason we see long-lived sclerophyllous leaves in a wide range of nutrient-poor environments (hard chaparral, bogs, montane forests, etc.).

Although there is a wide variety of plant types in montane systems, the nutrient poverty of soil may be the main reason we see forests dominated by coniferous forests with long-lived evergreen leaves. (Contrast eastern deciduous forests, which also experience snowy cold winters but grow on deeper, richer soil.) Some gymnosperms retain their needles only a few years, but some pines may retain their needles for decades.

Dealing with a short growing season

There are many ways of dealing with a short growing season. Short perennials, or mat plants, may extend their growing season by sheltering in the boundary layer of the ground, which heats up earlier in the spring. (This was discussed above.) Annuals must complete their life cycle quickly, and many of the mountain annuals do not get large. In many species, the short growing season has selected for early flowering, ensuring that the plant produces some seed before the winter sets in. This is discussed on the next page.