Fire in montane forest

Fire plays an important role in shaping the structure of montane forests.

Fire tolerance varies among species. Some trees have thick bark and survive low-intensity ground fires. Other tree species have thinner bark and are killed, even by low-intensity ground fires.

Fire tolerance varies with age. Even tree species that develop thick bark as adults are vulnerable to fire during the first few decades of their life. Seedlings and saplings (young trees) have thinner trunks, thinner bark, and leaves that are closer to the ground where they are more likely to be consumed in a ground fire.

Fire frequency and intensity

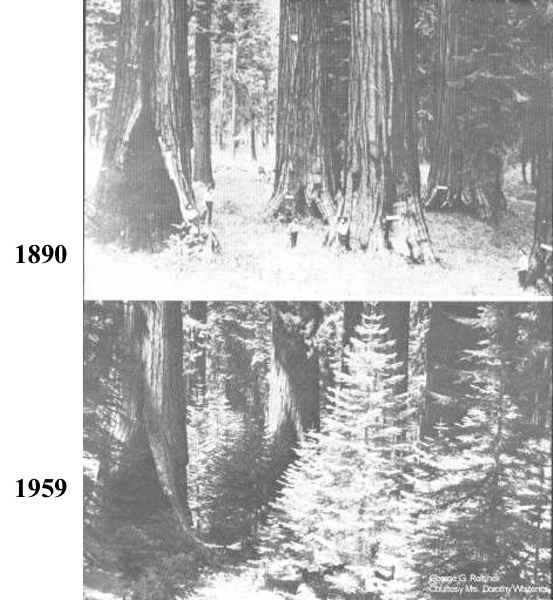

In many of California's montane forests, fire occurred more frequently than it has in recent decades, keeping the understory of the forest open and causing the fires that did occur to remain as low-intensity ground fires.

Giant sequoia (Sequioadendron giganteum) is a species that is particularly suited to a regime of low-intensity ground fires. Mature trees have very thick bark, so they survive ground fires. Additionally, the seeds require open mineral soil to germinate and establish seedlings. This means that seedlings only establish after leaf litter and duff (partially decomposed leaf litter) has burned off. Fire-suppression policies of the 1900s allowed encroachement of more fire sensitive species, such as firs (genus Abies) into the giant sequoia groves, providing "ladder fuels" that would carry flames up into the crowns of the giant sequoias, potentially killing them, and creating conditions that suppressed regeneration of the big trees. The photos below are from the National Park Service's archives.

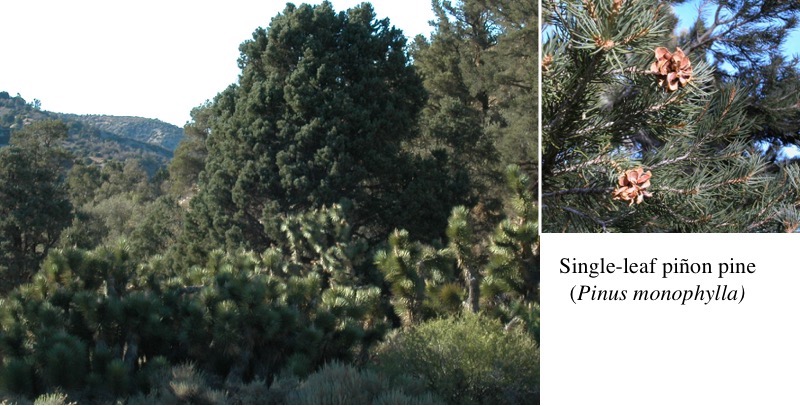

It is important to remember that not all conifers are tolerant of fire. Piñon pines, which dominate forests on the dry, transmontane side of California's major mountain range, have thin bark and do not tolerate even low intensity ground fires.

From your previous lesson (Week 6)

...pinyon pines do not tolerate fire well. Mature pinyon pine trees do not have bark that is thick enough to protect them, and even low-intensity ground fires will kill the trees. Researchers from UC Riverside have estimated that, historically, pinyon pine forests in southern California burned, on average, only once every 480 years. They also estimated that it took 100-150 years for a burned pinyon pine woodland to recover enough to look the way it did before a fire (Wangler and Minnich, 1996). As a result, using prescribed fire is probably not a good way to manage pinyon pine forests if the objective is to keep the pinyon pine forest healthy.

Serotiny

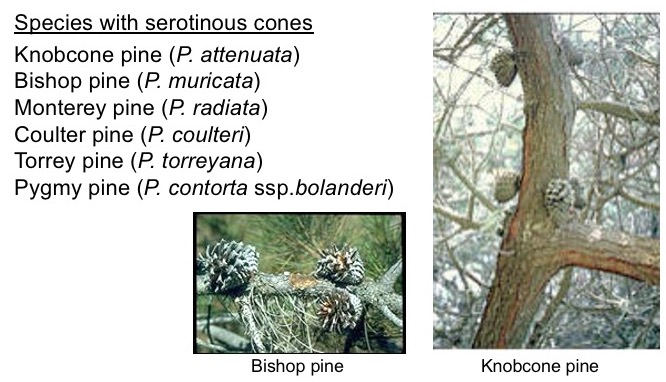

Serotiny is a characteristic of many fire-adapted conifers. Serotinous cones stay on the tree for many years, and their cone scales do not separate to release their seeds until they are heated. This allows cones to release seeds right after fire. Seedlings then enjoy an environment that is open and fairly free from competition.

In most cases, trees with serotinous cones are not fire-tolerant. They die in fires and the persistence of the species on the site depends on post-fire regeneration from seedling establishment.

There are several pine species with serotinous cones in California. You can tell if a tree has serotinous cones by looking at the placement of the cones on the tree. If a tree drops its cones or disperses its seeds soon after they mature, you will only see mature seed cones near the ends of branches. If the cones remain on the tree for many years, delaying seed release (i.e, they are serotinous), you will see cones that are still attached to older sections of stems.

Three things to note about species with serotinous cones.

- Cones will often open after remaining attached to the tree for many years, even if they have not experienced a fire.

- In some regions, the ground is hot enough during summer that it will stimulate cone opening if the cone drops to the ground.

- In some species, notably Pinus coulteri, some populations have serotinous cones and some do not. Researchers have speculated that the presences or absence of serotiny in a population is related to differences in the fire histories of individual sites.

Check your understanding:

And consider: